Attacking Cache Microarchitecture using PRIME+PROBE

Introduction

I have recently been very interested in computer architecture and low-level systems programming. One particular area of interest is in secure hardware design. What are current vulnerabilities in hardware microarchitectures, and how can we mitigate attacks that take advantage of these vulnerabilities?

One such microarchitecture attack is known as PRIME+PROBE. PRIME+PROBE takes advantage of cache side-channels to track how a victim accesses the cache. By doing so, an attacker can gain valuable information about the victim process.

Cache Architecture

In this project, I successfully hacked into a remote linux (ubuntu) environment oprerating with two Cascade Lake (CSL/CLX) CPUs.

Before diving into the attack itself, I’ll give a brief summary of cache architecture. When you run a program or process on your computer, your CPU must fetch, decode, and execute instructions. In order to do this, the CPU must access your main memory (DRAM). This lookup can often be slow (especially slow in the case of a page fault). To decrease latency, caches store frequently used data that the CPU can quickly access.

Caches are partitioned into different levels of increasing size. L1 and L2 caches are smaller, but have the lowest latency when accessed. L3 caches are slightly larger and slower to access, and are (typically) the last cache level before your computer’s DRAM. When accessing a cache, a cache hit occurs when the data you are looking for resides in the cache. A cache miss is the opposite. Upon a cache miss, the CPU must access the next level of cache (or DRAM) and fetch whatever data it’s looking for. After fetching, the CPU then loads that data into the L1 cache according to the Least Recently Used (LRU)] replacement policy.

Caches may have different organizations, however the most common is a set-associative cache. Here, the cache can be thought of as a table where rows are called “sets” and columns are “ways.” Given a memory address, one can infer the desired set lookup number and check every way to see if the desired data is held in the cache. To understand PRIME+PROBE, a detailed knowledge of cache architecture is required and I encourage anyone interested to read more.

On Cascade Lake (CSL/CLX) CPUs, the block size is 64 bytes. Cache dimensions are found in the following table.

| Cache | Cache Line Size | Total Size | Associativity | Number of Sets | Raw Latency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1-D | 64 | 32768 | 8 | 64 | |

| L2 | 64 | 1048576 | 16 | 1024 | |

| L3 | 64 | 37486592 | 11 | 53248 |

PRIME+PROBE

This attack works as follows:

- The attacker accesses a memory buffer along certain intervals so as to fill an entire set in the L2 cache with malicious data. This is the PRIME.

- When a victim process accesses the same set line in the L2 cache, there will be a cache miss, and it will evict some of our maliciously placed data to the L3 cache (or DRAM if there have been enough accesses).

- We check all malicious data addresses and measure the latency of returned data. If our latency is above a certain threshold, we can infer that it has been evicted from the L2 cache indicating that someone has accessed our set. This is the PROBE.

Overall, the attack is simple. In practice, it is difficult due to the amount of potential noise, the inability to fully understand cache optimizations, and the difficulty in ensuring accurate virtual-to-physical memory address translations.

To first address virtual-to-pysical memory address translations, we use memory page sizes of 2MB. This is because we want to have full control over our set access bits in physical memory. Recall that virtual adresses share bits with physical addresses in the virtually-indexed, physically tagged (VIPT) cache architecture. As such, we want to have a large enough page size such that we can index into all 1024 sets in the L2 cache reliably.

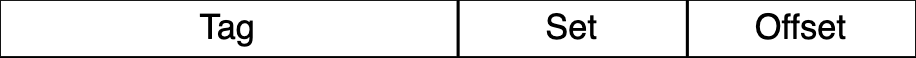

Addresses look like this to the cache:

And like this to the paging hierarchy:

An additionally issue to overcome is the presence of cache prefetching, a hardware optimization that prefetches data that follows predictable access patterns. To avoid this problem, all memory accesses must be made at random (random set orders, random way orders, etc.)

Lastly, tracking evictions can be susceptible to a lot of noise from other processes running on the victim machine (including my own attacking code). To mitigate noise, it’s really important to keep data on the stack.

Using these tips, combined with some smart latency threshold tuning, I was able to successfully read a victim processes repeated acesses to its L2 cache.